How to Structure Sentences in German (Includes Tips & Tricks)

The structure of simple German sentences is quite similar to English sentences: SUBJECT – VERB – OBJECT. An important difference in comparison to English sentence structure is that the verb always takes the second position in main clauses. This is true even if the subject is not in the first position.

Oftentimes, a German sentence starts with an adverb of time. This sentence will always be followed by a verb with the subject coming third: ADVERB OF TIME – VERB – SUBJECT + the rest of the sentence. The adverb of time and the subject can switch positions as long as the verb stays in the second position.

However, as German sentences become more complex, the German syntax can get a bit tricky. Suddenly, you might encounter a main verb at the very end of the sentence, leaving you wondering why.

If your goal is to engage in meaningful conversations in German beyond just greetings like “Guten Tag!” and “Wie geht’s?”, it’s crucial to familiarize yourself with the intricacies of German sentence structure. Once you understand the German grammar rules that dictate how German sentences are constructed, you’ll feel much more at ease when speaking to native German speakers.

In this article, we will delve into the rules of German sentence structure, help you avoid common mistakes, provide authentic examples that frequently pop up in conversations, and offer tips and tricks for practicing German sentence structure effectively.

Basics of German Sentence Structure

When there is a subject, a verb, and an object in a German sentence, the translation is straightforward: simply follow the English word order with the subject at the beginning, followed by the verb, and then the direct object.

Here are some examples of German sentences with basic sentence structure and their English translations:

Ich sehe das Auto. → I see the car.

Sie hat einen Hund. → She has a dog.

Jenny braucht ein Ladekabel. → Jenny needs a charging cable.

Ich höre nichts. → I hear nothing.

Ich liebe dich. → I love you.

Time, Manner, and Place

When you add additional pieces of information about when, how, and where something happens, you will need to remember to put them in the following order: TIME – MANNER – PLACE.

Here are some simple declarative sentences showing this.

Ich bleibe [morgen] zu Hause. → I am staying at home tomorrow.

Ich fahre [morgen] [mit dem Zug]. → I am taking the train tomorrow.

Wir fahren [morgen] [mit dem Zug] [nach Berlin]. → We are taking the train to Berlin tomorrow.

Sie spricht [ziemlich gut] Deutsch. → She speaks German pretty well.

Sie ist [ohne zu zögern] [ins Auto] gestiegen. → She got into the car without hesitating.

German Sentences with Auxiliary Verbs

The subject-verb-object rule no longer applies when auxiliary verbs are introduced in German. Auxiliary verbs are used in the Perfect, the Future and the Past Perfect tenses, as well as in the Subjunctive and the Passive Voice constructions.

In the Perfect (Perfekt) and Past Perfect (Plusquamperfekt) tenses, the conjugated verb takes the second position in the sentence, while the past participle is placed at the end.

Ich habe ihn gestern beim Bäcker gesehen. → I saw him at the bakery yesterday.

Nelio ist ins Wasser gesprungen. → Nelio jumped into the water.

Sebastian hatte mir ein paar gute Tipps gegeben. → Sebastian gave me some good tips.

Nadine und Maik waren pünktlich in München gelandet. → Nadine and Maik landed in Munich on time.

The same rule applies to the Subjunctive and Passive constructions.

Ich hätte ihn vom Bahnhof abgeholt. → I would have picked him up from the train station.

Sie wurde von ihrem Vater zur Schule gebracht. → She was brought to school by her father.

In the Future tense, the conjugated verb is in the second position as well, while the infinitive is at the end of the sentence.

Ich werde ihn niemals vergessen. → I will never forget him.

Die Schülerin wird sich das YouTube-Video angucken. → The student will watch the YouTube video.

German Sentences with Modal Verbs

The structure of German sentences with modal verbs is similar to those with auxiliary verbs. Modal verbs are typically paired with an infinitive which is positioned at the end of the sentence. The modal verb has to be conjugated accordingly.

Ich muss morgen um 6 Uhr aufstehen. → I have to get up at 6 am tomorrow.

Sarah möchte eine Pause machen. → Sarah would like to take a break.

Jacqueline kann uns heute Abend helfen. → Jacqueline can help us tonight.

Structuring Questions in German

Questions in German start with either a verb or a question word followed by the subject of the sentence. Just like in statements, the past participles and infinitives are positioned at the end of a German question. The following YouTube video will go more into detail on what to watch out for when asking questions in German.

Gehst du jetzt nach Hause? → Are you going home now?

Ist er zur Arbeit gefahren? → Did he drive to work?

Wann kommt er zurück? → When is he coming back?

Warum hat er dich belogen? → Why did he lie to you?

The Verb is in the Second Position (Avoid Making These Common Mistakes)

The verb always takes the second position in main clauses. The sentence could start with the subject and be followed the verb and an adverb of time:

Ich gehe morgen in den Park. → I am going to the park tomorrow.

Ich fahre am Samstag zum Flughafen. → I am driving to the airport on Saturday.

Es wird in den nächsten paar Tagen kalt. → It will be cold in the next few days.

But you can also switch the adverb of time and the subject if you want to put emphasis on the time.

Morgen gehe ich in den Park. → Literally: Tomorrow go I into the park. It is incorrect to say: Morgen ich gehe in den Park. This is a very common mistake, particularly made by native English speakers.

Am Samstag fahre ich zum Flughafen. → Literally: On Saturday drive I to the airport. It is incorrect to say: Am Samstag ich fahre zum Flughafen.

In den nächsten paar Tagen wird es kalt. → In the next few days, it is going to be cold. The verb is the sixth word of the sentence but takes the second position because the adverb of time is made up of more than one word.

Learn more about the position of verbs in main clauses by watching the following YouTube video.

German Sentence Structure with Direct and Indirect Objects

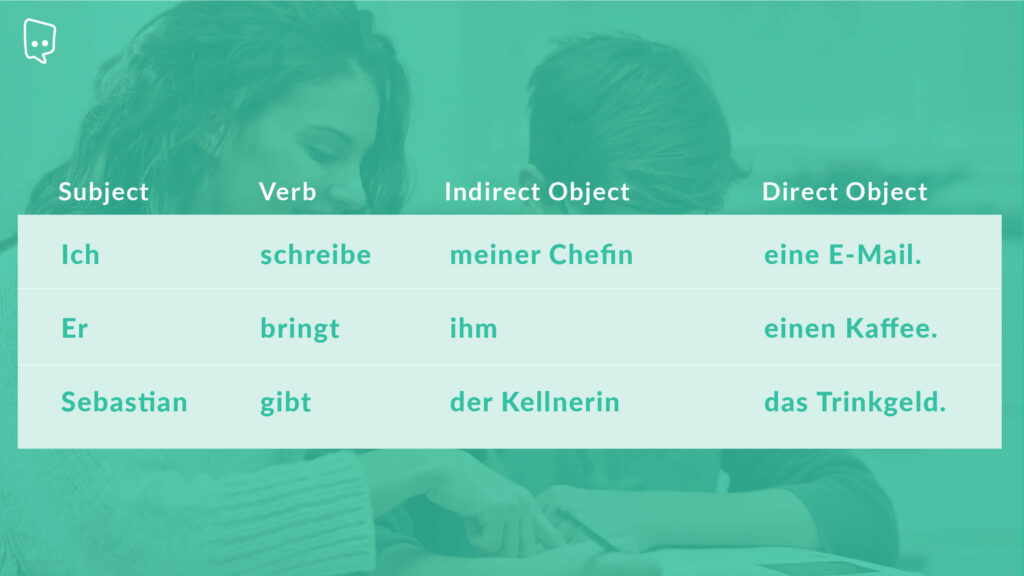

Some verbs in German can be used with a direct (accusative) and indirect (dative) object. Such verbs include: schreiben, zeigen, bringen, geben, and empfehlen. In these sentences, the indirect object comes before the direct object.

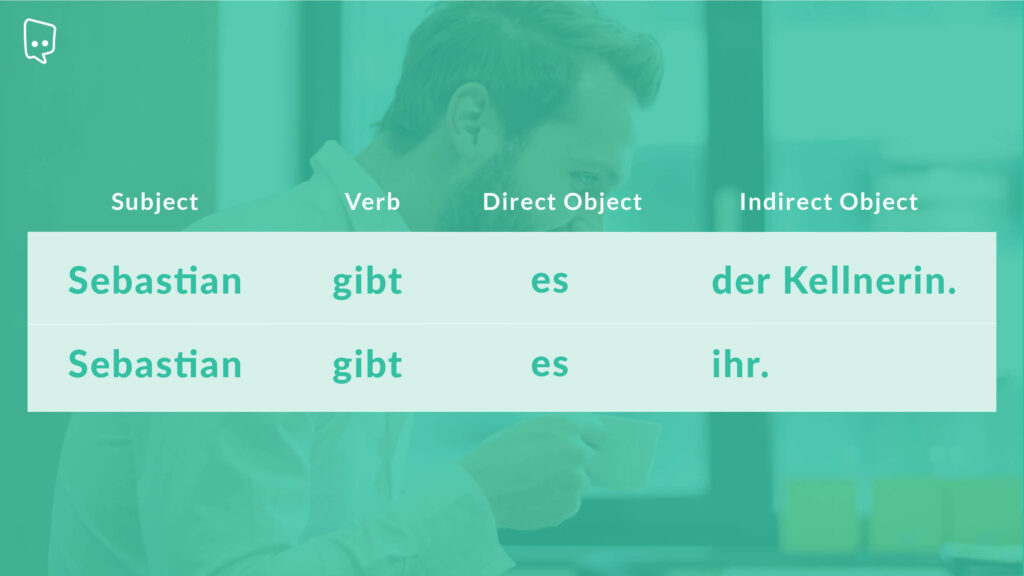

However, if the direct object is a pronoun, the direct and indirect object switch positions in the sentence. The direct object now comes first.

Separable Verbs

Some German verbs have prefixes that can be separated from the verb. These separable prefixes include ab-, vor-, zu-, auf-, ein-, and zurück. In the present (Präsens) and in the preterite (Präteritum) tense, you need to place the prefix of the verb at the end of the main clause.

Ich mache das Fenster auf. → I am opening the window.

Er kommt um halb drei aus Berlin zurück. → He is coming back from Berlin at 3:30 pm.

Coordinating Conjunctions

The coordinating conjunctions und, denn, sondern, aber, and oder simply connect to main clauses in German.

Ich esse Waffeln und ich trinke einen Kakao. → I am eating waffles and drinking hot chocolate.

Ich gehe duschen, denn ich habe geschwitzt. → I am going to go take a shower because I have been sweating.

Wir haben nicht geschrieben, sondern wir haben telefoniert. → We didn’t write to each other but we talked on the phone.

Er ist sauer auf mich, aber ich weiß nicht warum. → He is mad at me but I don’t know why.

Gehst du ins Bett oder guckst du noch einen Film mit mir? → Are you going to bed or are you still going to watch a movie with me?

Creating Complex German Sentences with Subordinating Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunctions may confuse some German learners because they have an influence on the structure of the clause that follows the conjunction. The 20 most important subordinating conjunctions you need to remember are:

- als when

- bevor before

- bis until

- da since, as

- damit so that

- dass that

- ehe before

- falls in case

- indem by

- nachdem after

- ob whether

- obwohl although

- seit, seitdem since

- sodass consequently, thus

- während while

- wann when

- weil because

- wenn if, when

- sobald as soon as

- solange as long as

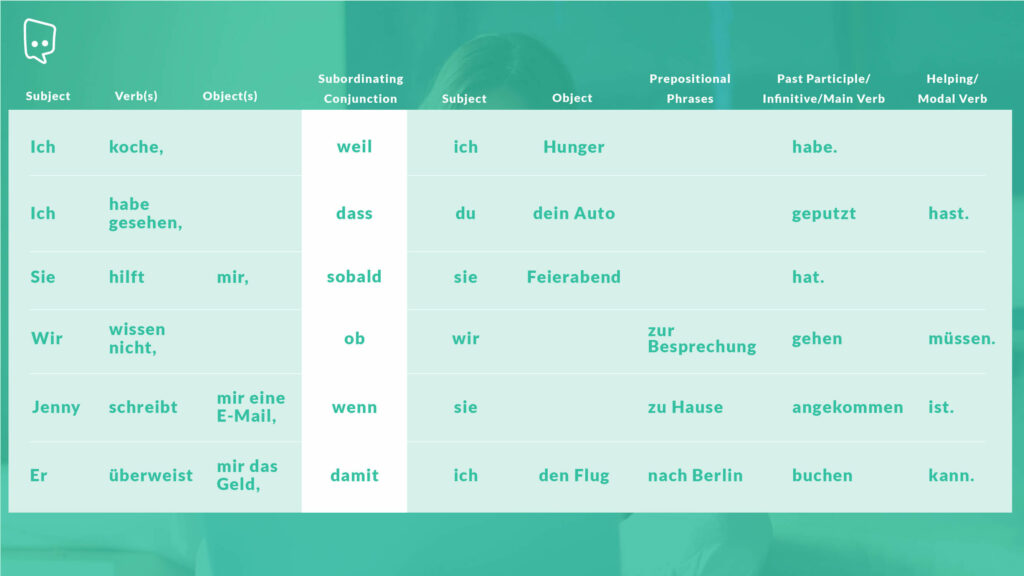

Clauses that begin with a subordinating conjunction are called subordinating clauses. In these clauses, you need to position the verb at the very end. If the subordinating clause includes a helping or a modal verb, it needs to be positioned at the end, following the past participle or infinitive.

Here are examples where the main clause maintains the subject-verb-object sequence, followed by a subordinate clause. Both clauses are separated by a comma.

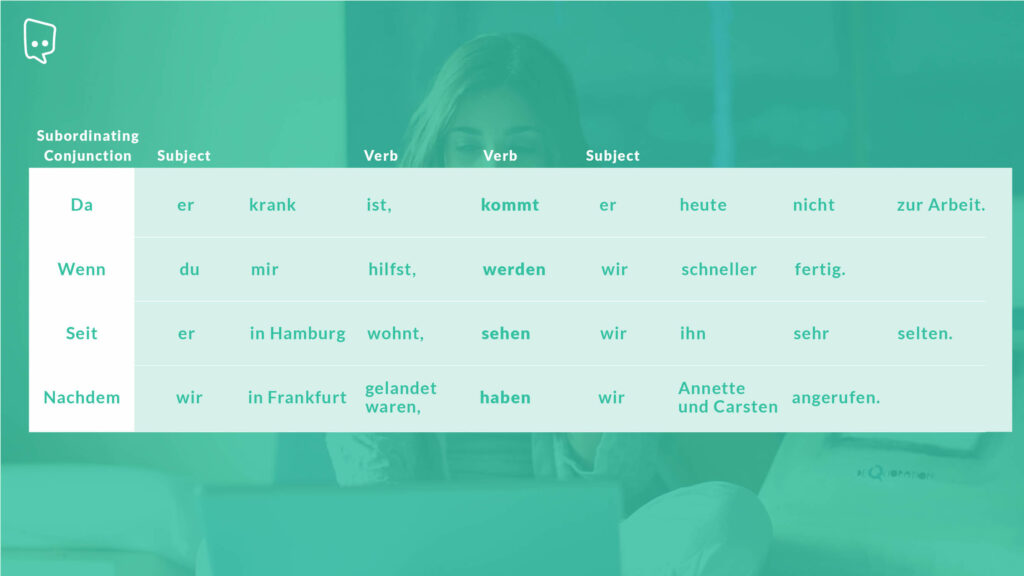

It is also possible to have the subordinating clause at the beginning, followed by the main clause. In this case, you need to remember to place the verb right after the comma. The subject and verb switch positions.

This mirrors the principle we previously discussed, where the verb consistently occupies the second position in a German sentence. In this setup, the entire subordinating clause occupies the first position.

Negations in a German Sentence

You can negate German sentences using “nicht” or “kein”, depending on whether you are negating actions or nouns, respectively. You can find a very detailed explanation in the video below.

Nicht with Verbs

In general, nicht follows the conjugated verb.

Ich bleibe nicht. → I am not staying.

Jenny geht nicht nach Hause. → Jenny is not going home.

Nicht with Separable Verbs

If you want to negate a separable verb, you have to remember that “nicht” is placed before the separable prefix.

Ich rufe ihn morgen nicht an. → I am not calling him tomorrow.

Sie fährt morgen früh nicht zurück. → She is not driving back tomorrow morning.

Nicht with Direct and Indirect Objects

Another important rule you have to remember is that “nicht” follows the direct or indirect object.

Ich verstehe das nicht. → I don’t understand that.

Wir sehen ihn nicht. → We don’t see him.

Sie vertraut mir nicht. → She doesn’t trust me.

Nicht with the Verb “Sein”

You also have to remember that “nicht” always follows the verb sein.

Das ist nicht Herr Maier. → This is not Mr. Maier.

Nicht with Compound Tenses

With compound tenses (includes the Perfect and Future Tense as well as Modal Verbs), “nicht” precedes the full verb at the end.

Er hat ihm gestern Nachmittag nicht geholfen. → He did not help him yesterday afternoon.

Er muss sich morgen nicht entscheiden. → He doesn’t have to decide tomorrow.

Nicht with Time, Manner, and Place

“Nicht” precedes the preposition that goes with time, manner, and place.

Wir kommen nicht um 20 Uhr an. → We are not arriving at 8 pm.

Die Kinder sind heute nicht zur Schule gegangen. → The children are not going to school today.

Nicht with Adjectives and Adverbs

“Nicht” precedes adjectives and adverbs.

Er fährt nicht schnell. → He is not driving fast.

Der Salat sieht nicht lecker aus. → The salad doesn’t look delicious.

Er tanzt nicht gern. → He doesn’t like to dance.

Es dauert nicht lange. → It doesn’t take long.

Sie hat nicht sofort geantwortet. → She did not answer immediately.

Kein with Nouns

“Kein” precedes the noun.

Er hat keine Tochter. → He doesn’t have a daughter.

Alina möchte keinen Apfel essen. → Alina doesn’t want to eat an apple.

Wir haben kein Geld. → We don’t have any money.

Das ist keine gute Idee. → That’s not a good idea.

Ich habe keinen Hunger. → I am not hungry.

Must Tips to Understand German Word Order

The three most important things you need to remember about German sentence structure are as follows:

- Always place the verb in the second position in a main clause. This does not necessarily mean that the verb will be the second word of the sentence.

- Remember that in subordinating clauses, the verbs need to be placed at the very end of the sentence.

- Place indirect objects before direct objects unless the direct object is a pronoun.

- Place “nicht” after the verb and place “kein” before the noun.

Conclusion

Try to become acquainted with the above rules and start analyzing the German sentences you are reading and identifying the verbs, the subjects, the objects, the conjunctions, the negations, the adjectives and adverbs, and the prefixes.

Try writing simple sentences of your own and pay close attention to the dictated German sentence structure. You’ll become a pro at it before you know it!